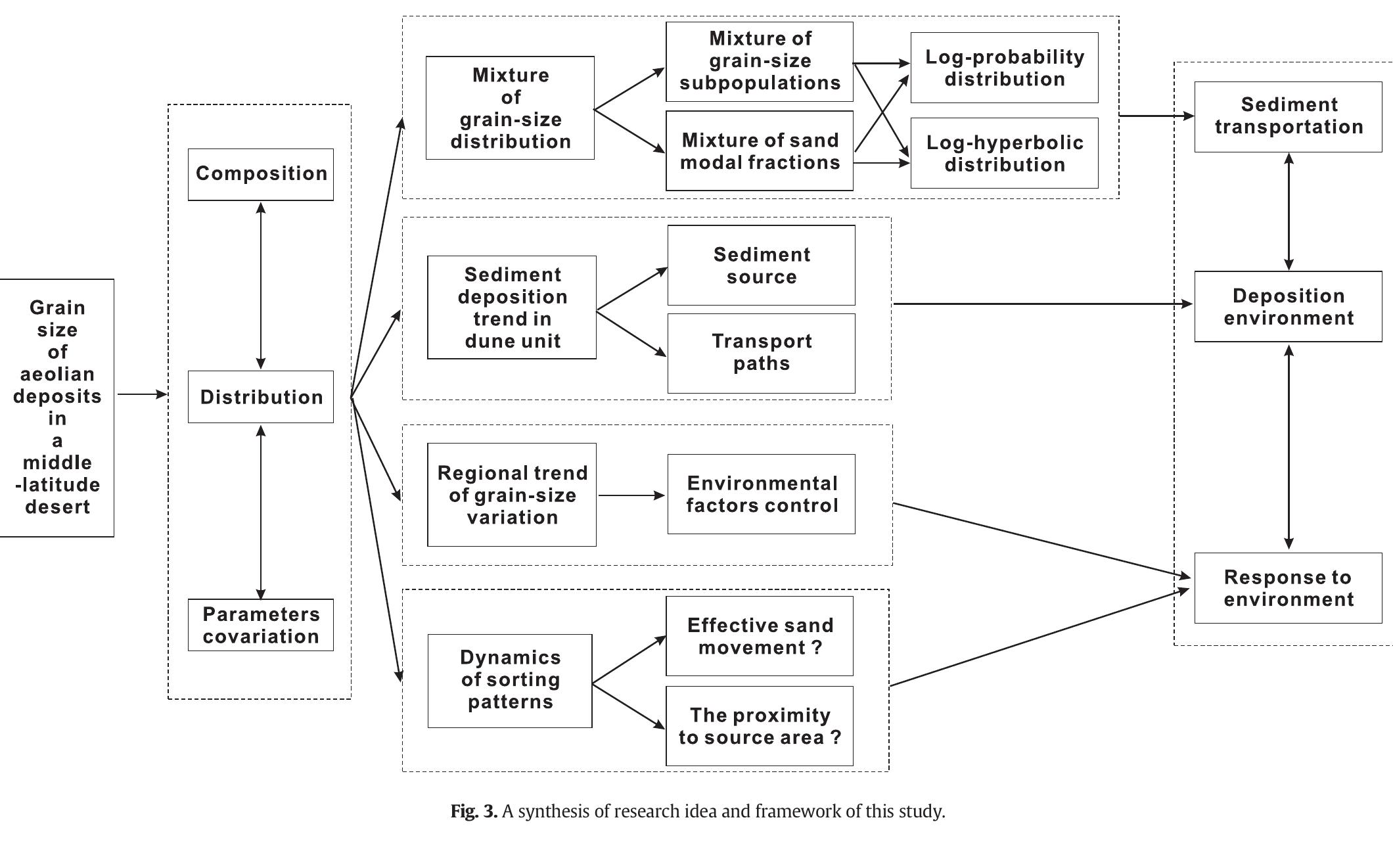

|

This article appeared in a journal published by Elsevier. The attached copy is furnished to the author for internal non-commercial research and education use, including for instruction at the authors institution and sharing with colleagues. Provided for non-commercial research and education use. Not for reproduction, distribution or commercial use.

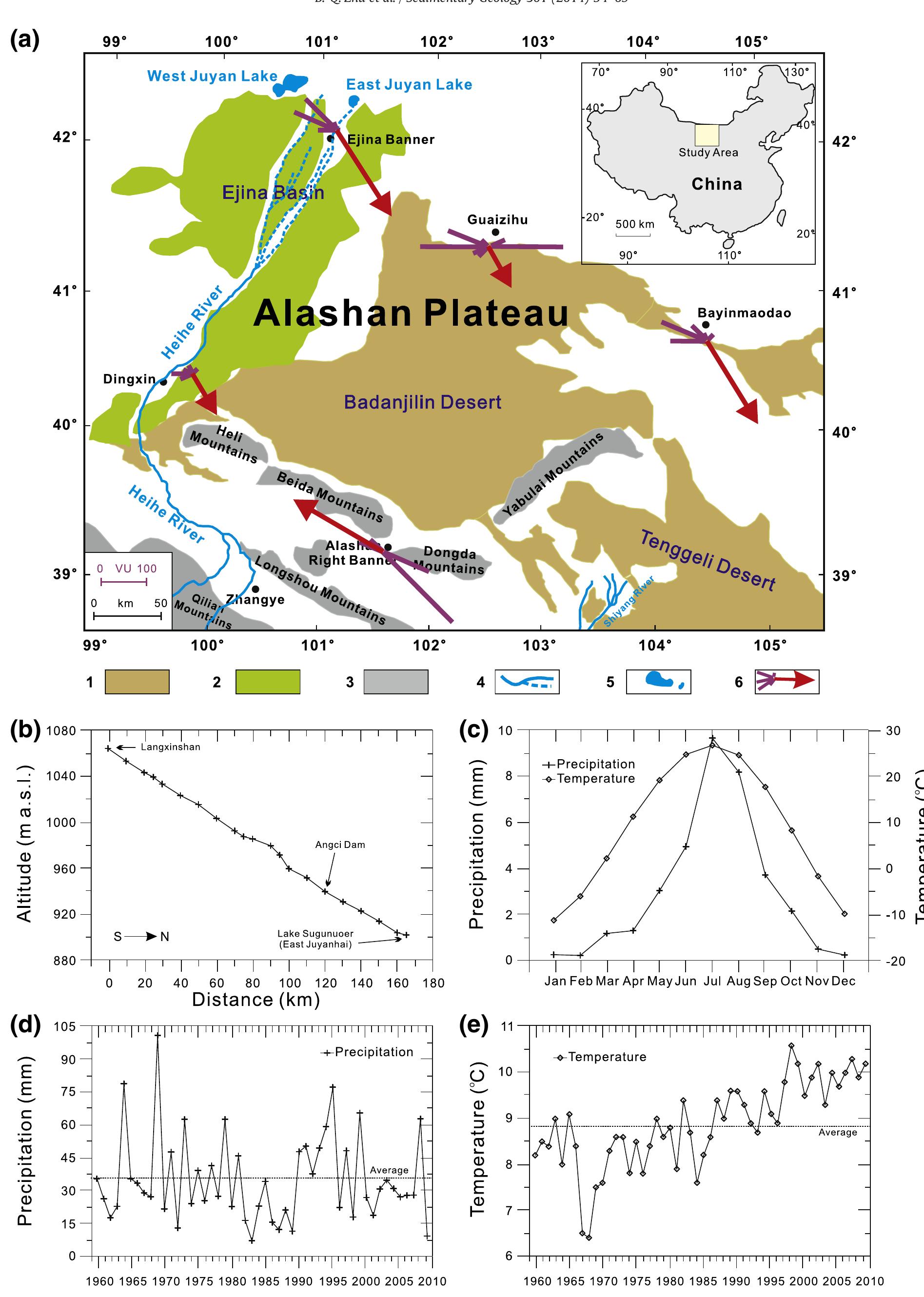

Fig. 1. (a) Overview of the landscape of the Alashan Plateau in northwestern China (modified from Yang et al., 2011) and (b) a relief profile of the S-N trending line (along the East river from Langxinshan to Lake Sugunuoer), (c) the seasonal distribution of multi-year average precipitation and temperature, variations of (d) the average annual precipitations and (e) tem- peratures (50 years during 1960-2009) in the Ejina Basin. The compound directions of wind systems in different areas in the Alashan Plateau are also shown in panel a. Legend: 1 sand dunes, 2 fluvial/alluvial sediments associated with the Heihe River, 3 adjacent mountain ranges, 4 rivers, 5 lakes, and 6 sand roses (Fryberger and Dean, 1979) for each of the five surround- ing weathering stations, with purple lines showing winds capable of transporting sand from various directions (DP, vector units with wind speed in knots VU) and red lines with arrows indicating the resultant sand transport trend (RDP, vector units in VU).

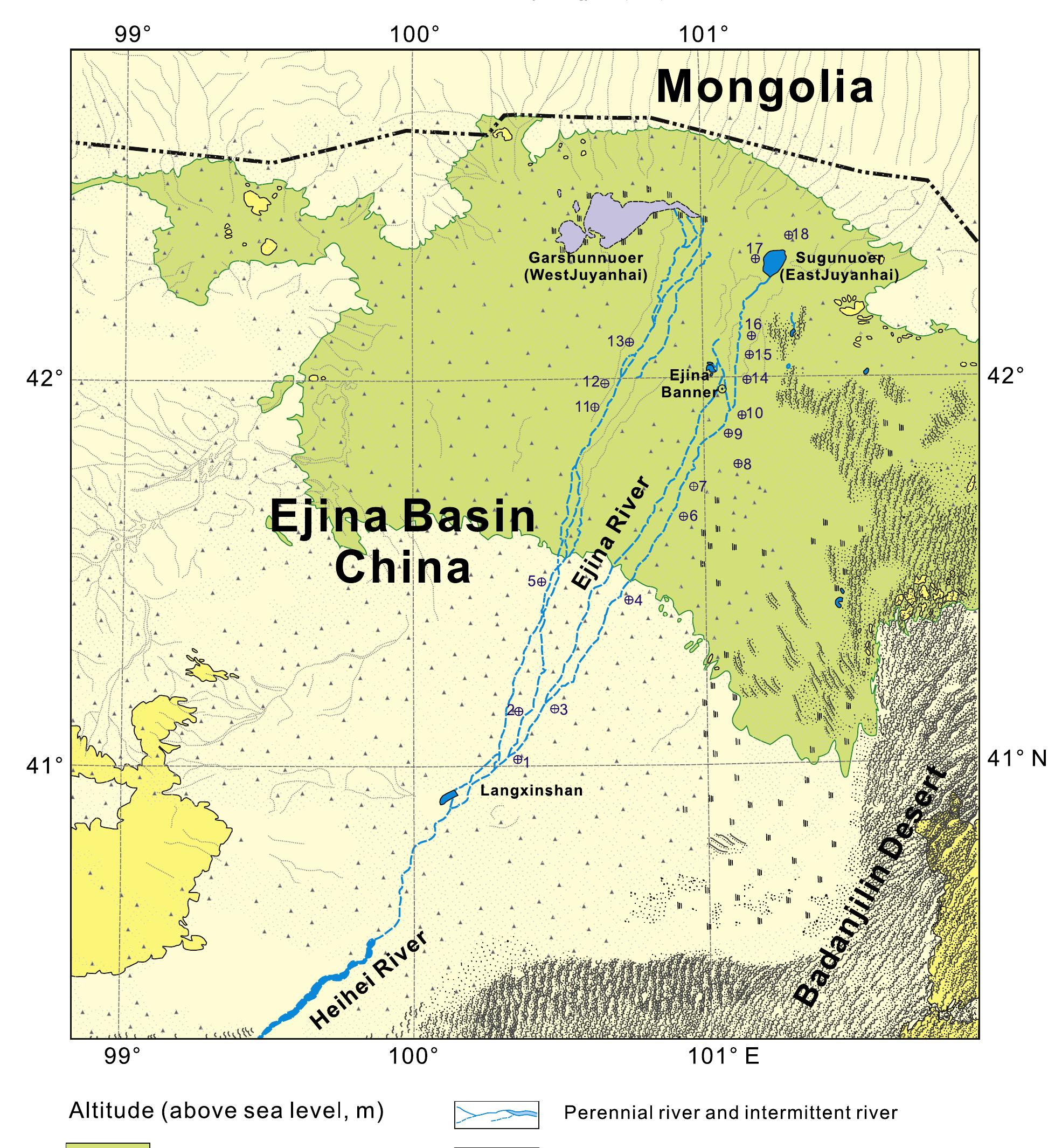

Grain size parameters and size fraction percentages in phi unit of the study samples in the Ejina. Table 1

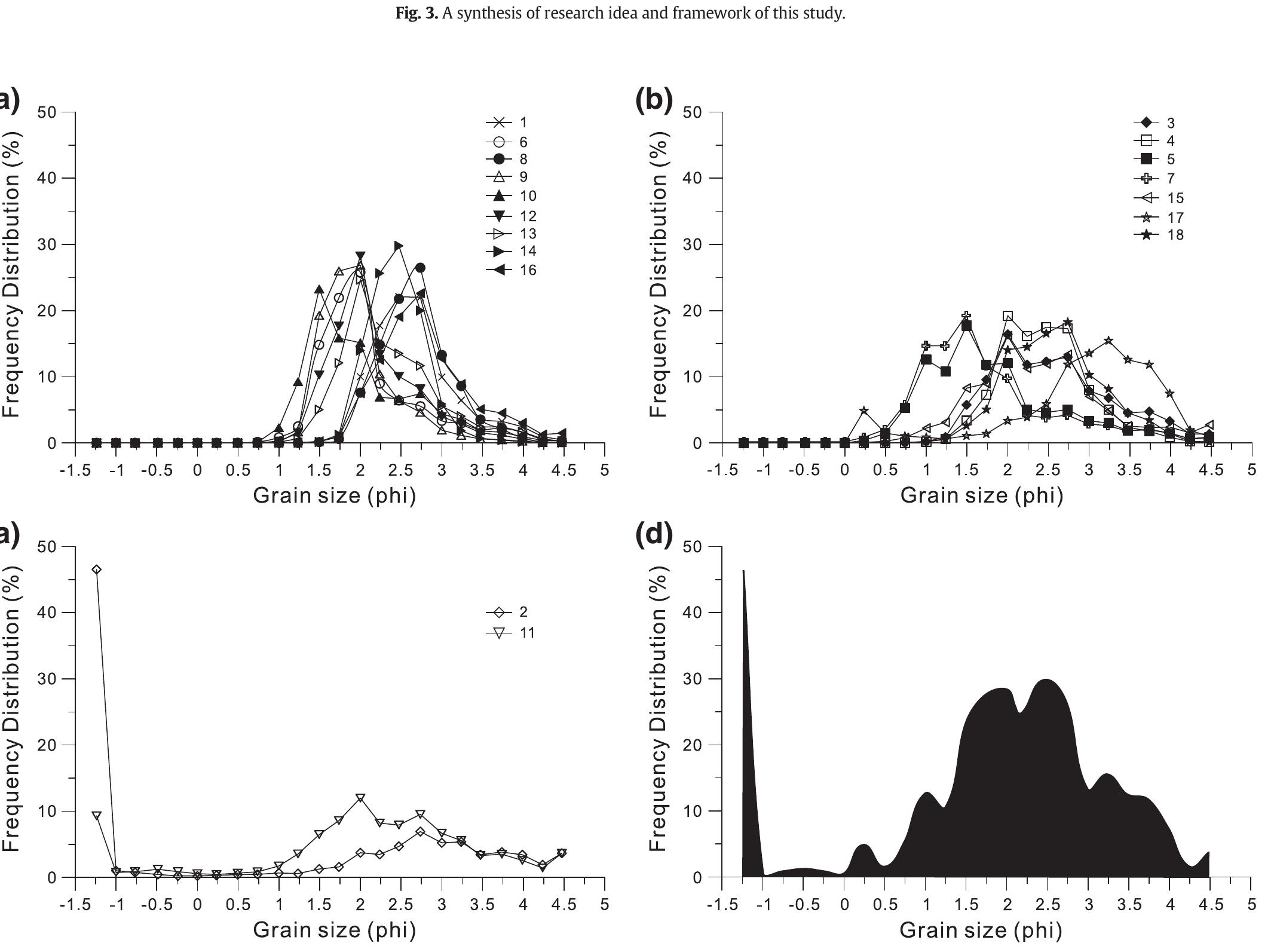

Fig. 4. Frequency curves of the proportion of grain-size fractions of (a) the dune crest sands and (b) interdune sands and (c) Gobi sands, and (d) the frequency distribution of the sa modes for the Ejina samples.

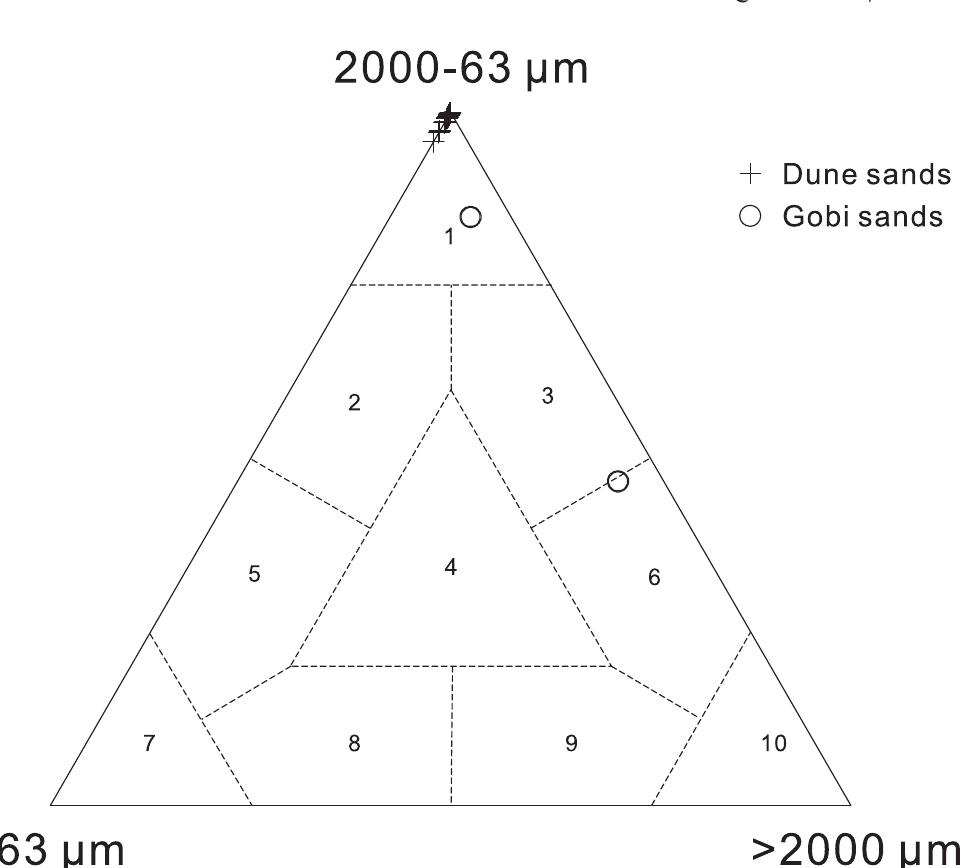

Fig. 5. Grain-size classification of the dune and Gobi sediments from the Ejina in Shepard's (1954) diagram. Fields indicate: 1 sand, 2 silty sand, 3 gravelly sand, 4 gravel-sand-silt, 5 sandy silt, 6 sand gravel, 7 silt, 8 gravel silt, 9 silt gravel, and 10 gravel.

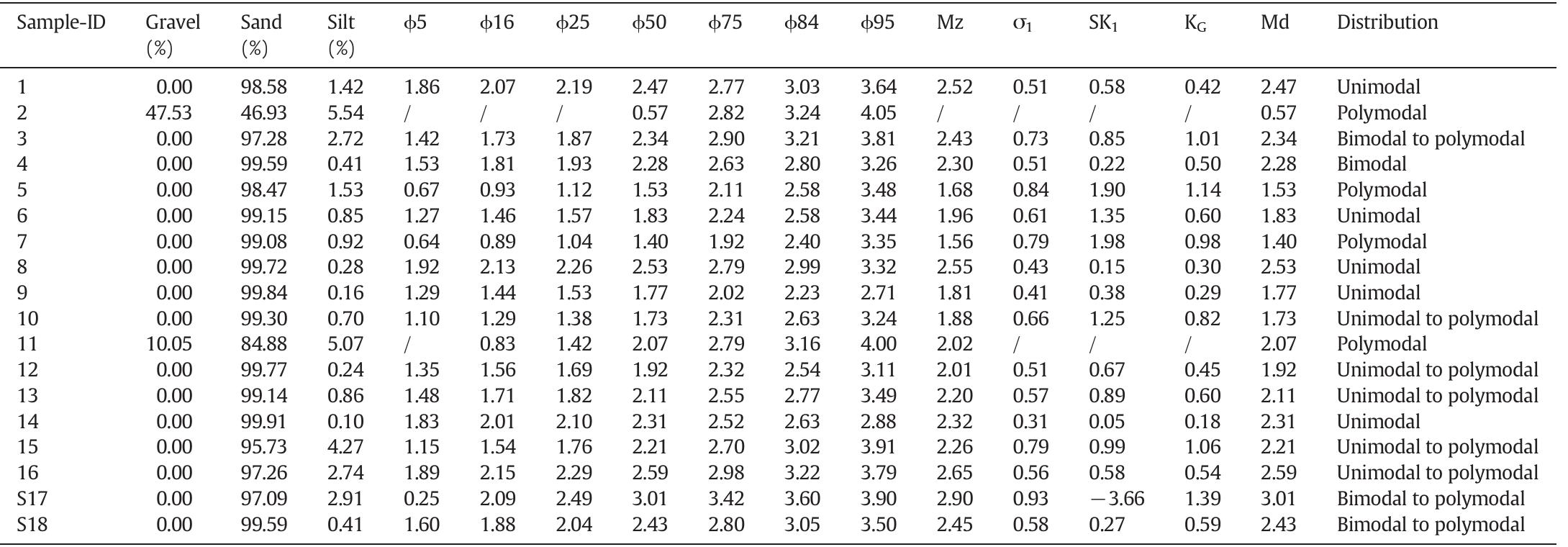

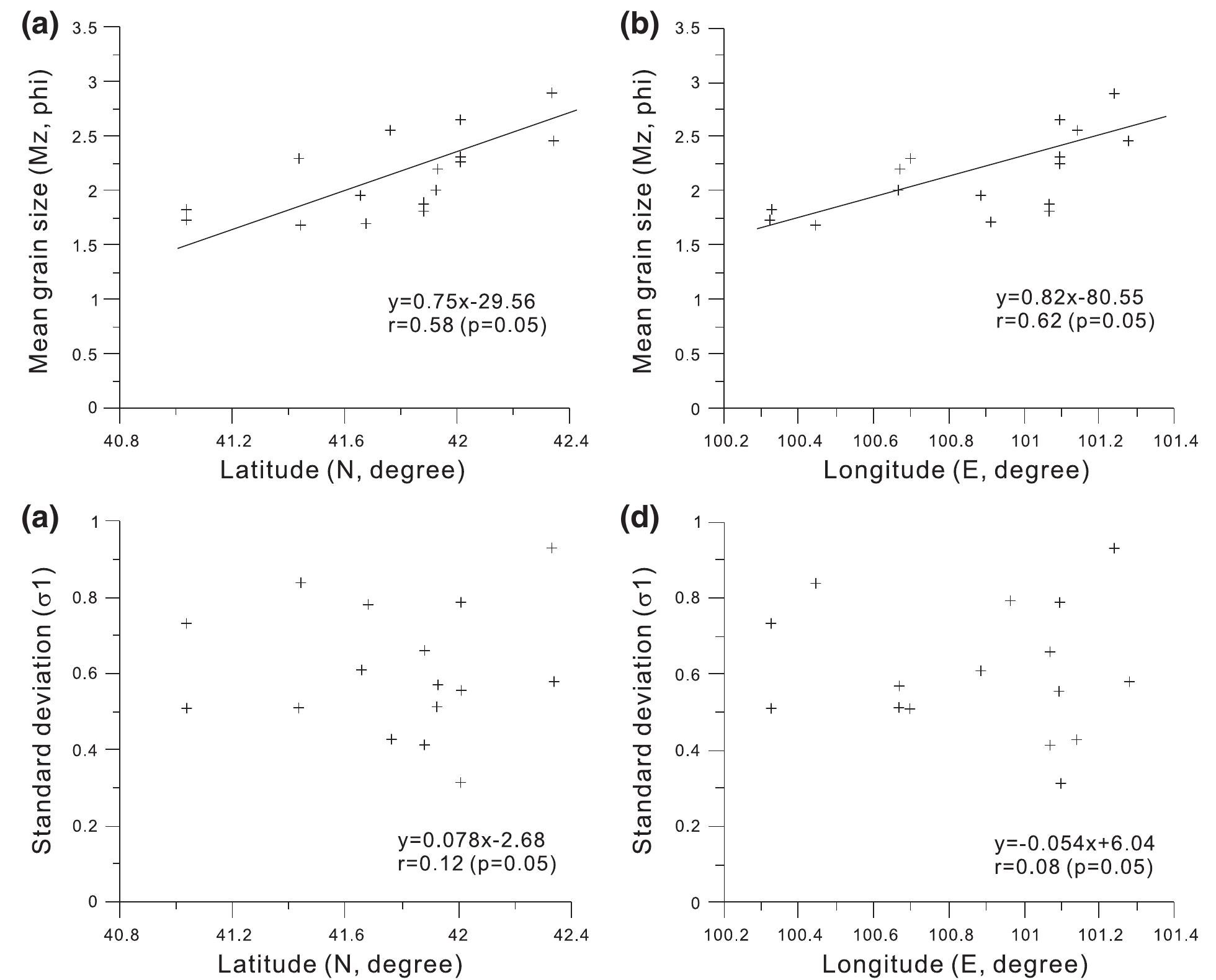

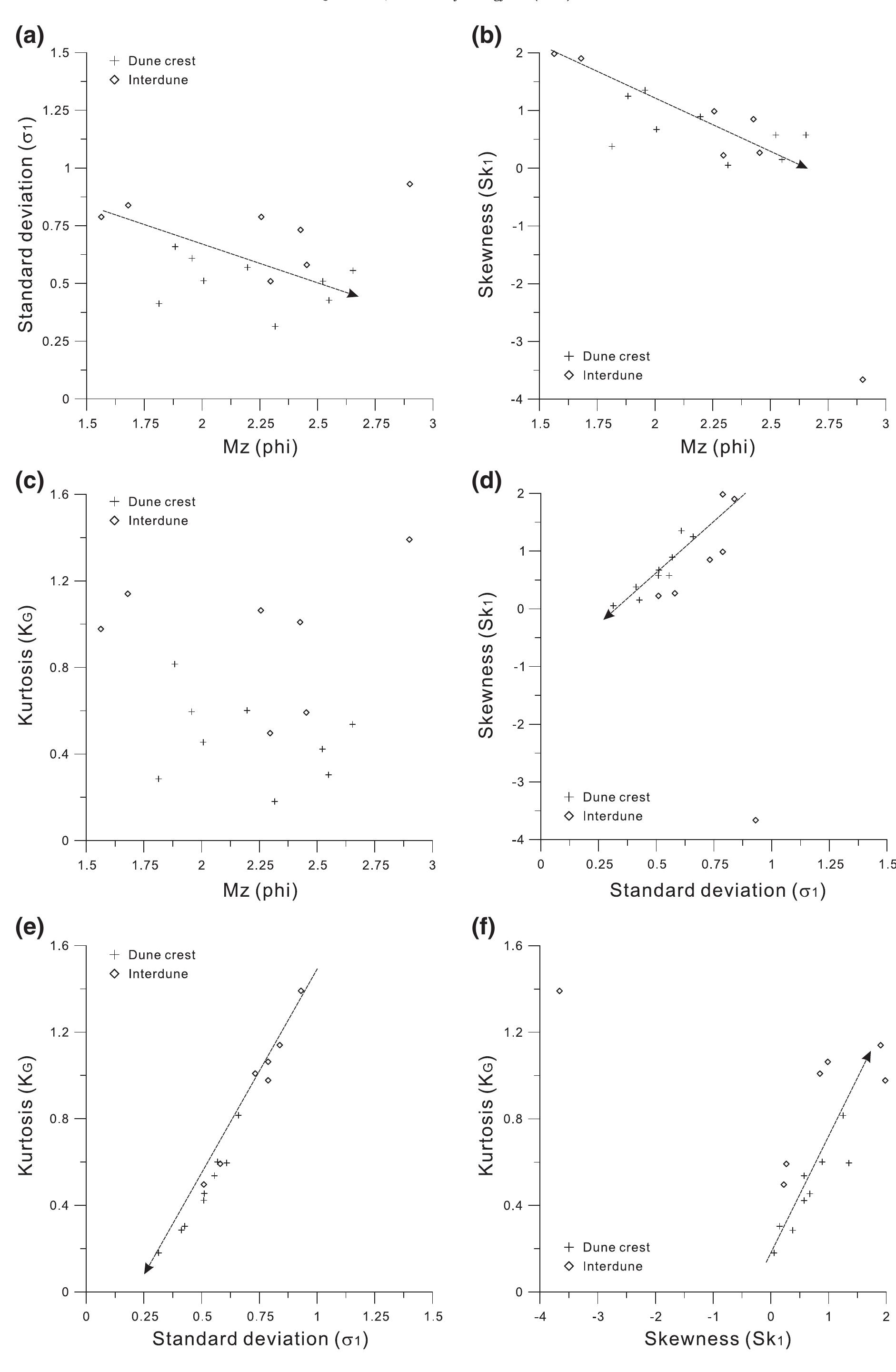

Fig. 6. Variation of Mz values with (a) latitude and (b) longitude degree, and sorting values (01) with (c) latitude and (d) longitude degree of dune sand samples in this study Skewness values (Sk, ) range widely from — 3.66 to 1.90 (Tables 1, 2) in the Ejina, belonging to strongly positively skewed to quite strongly In general, mean grain size (Mz) tends to decrease as sorting im- proves (Fig. 8a). The best sorting is attained by sediments with a mean size between 1.86 and 2.5. Skewness (SK,) tends to decrease, and even become negative as mean grain size decreases from dune to dune (Fig. 8b). In interdunes sands, there is a large range of grain sizes mixed by coarse and fine sands (Fig. 4b), in which the coarse fraction traps and protects fines from further movement. The mean size vs. kur- tosis diagram (Fig. 8c) shows a very scattered pattern and no trend can

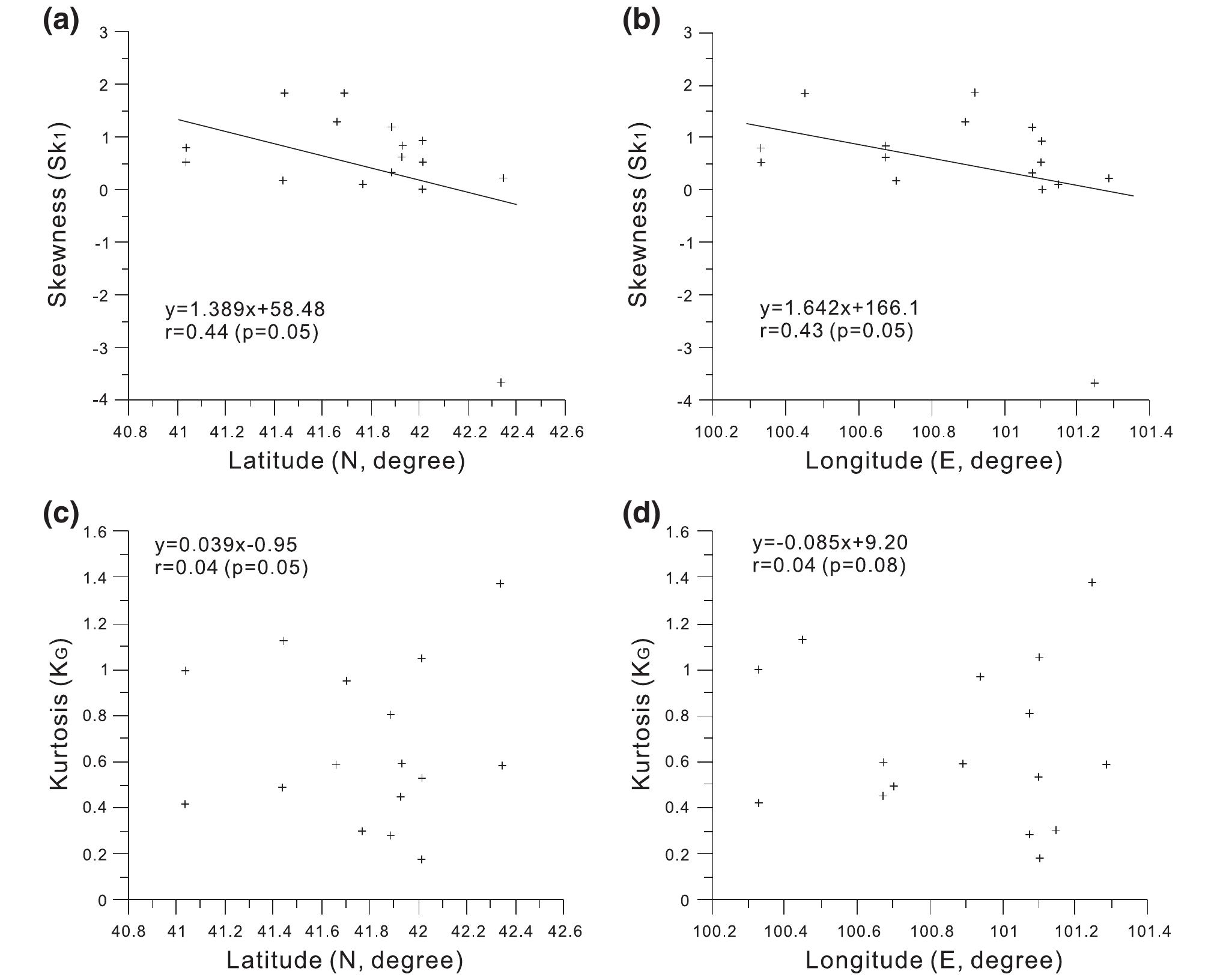

Fig. 7. Variation of the skewness values (Sk;) with (a) latitude and (b) longitude degree, and the kurtosis values (K¢) with (c) latitude and (d) longitude degree of dune sand samples in this study.

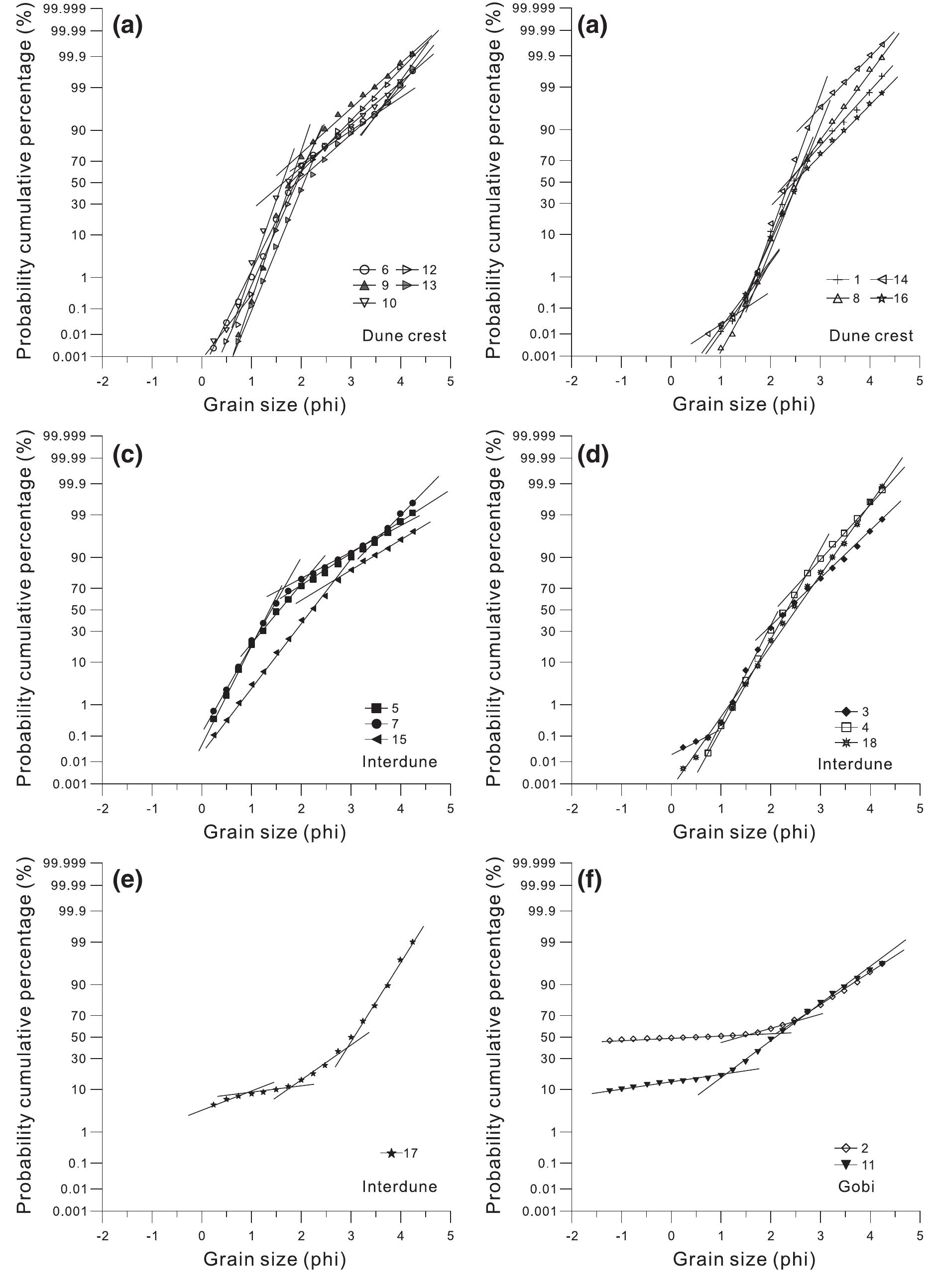

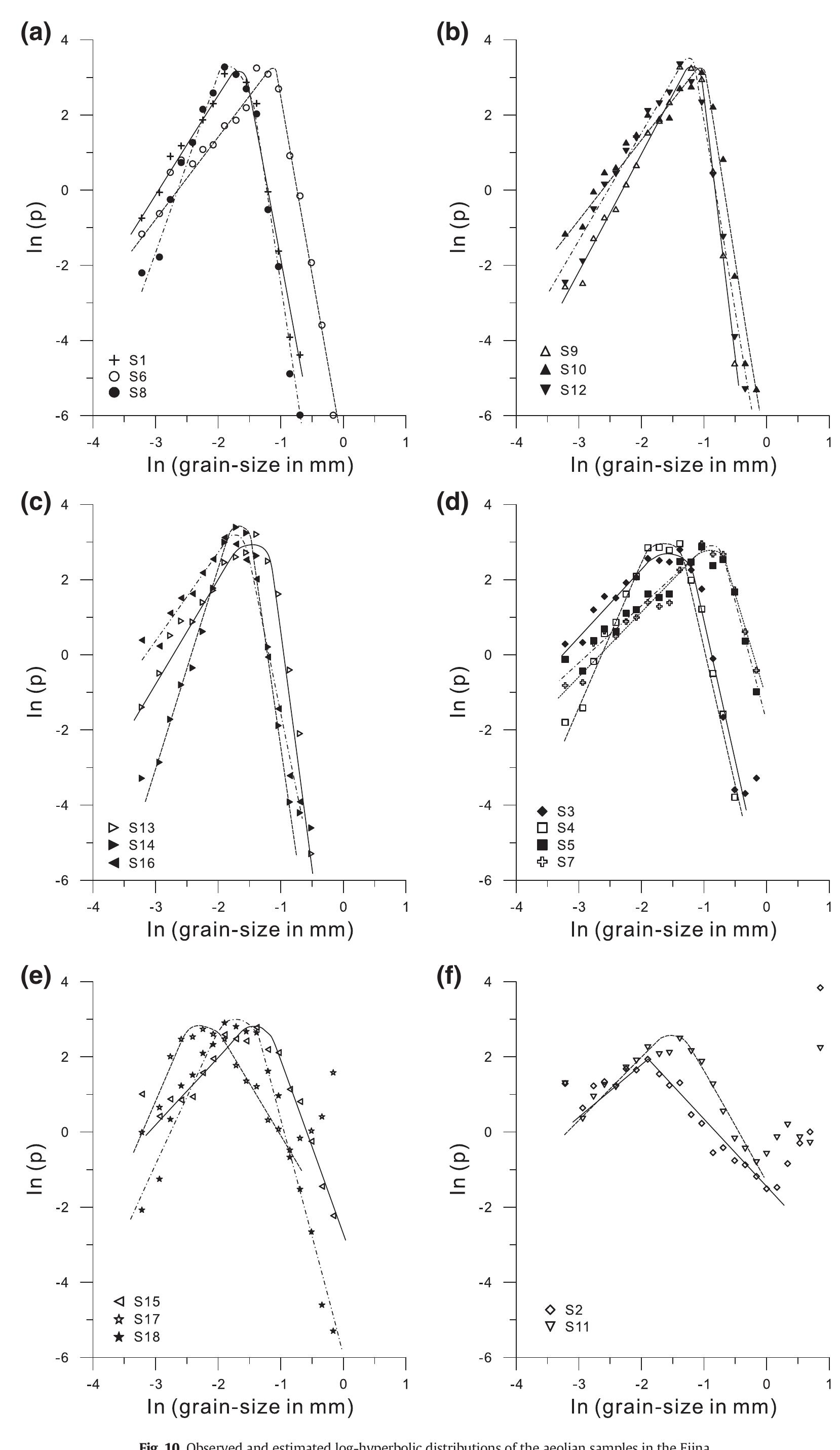

Fig. 9. The log-probability cumulative curves of the grain-size distribution of the dune crest sand samples (a and b), of the interdune sand samples (c, d, and e) and of the Gobi samples (f) i the Ejina. The similarity of curve shapes is evident, but variations in mean and maximum grain sizes and amounts of individual populations are illustrated.

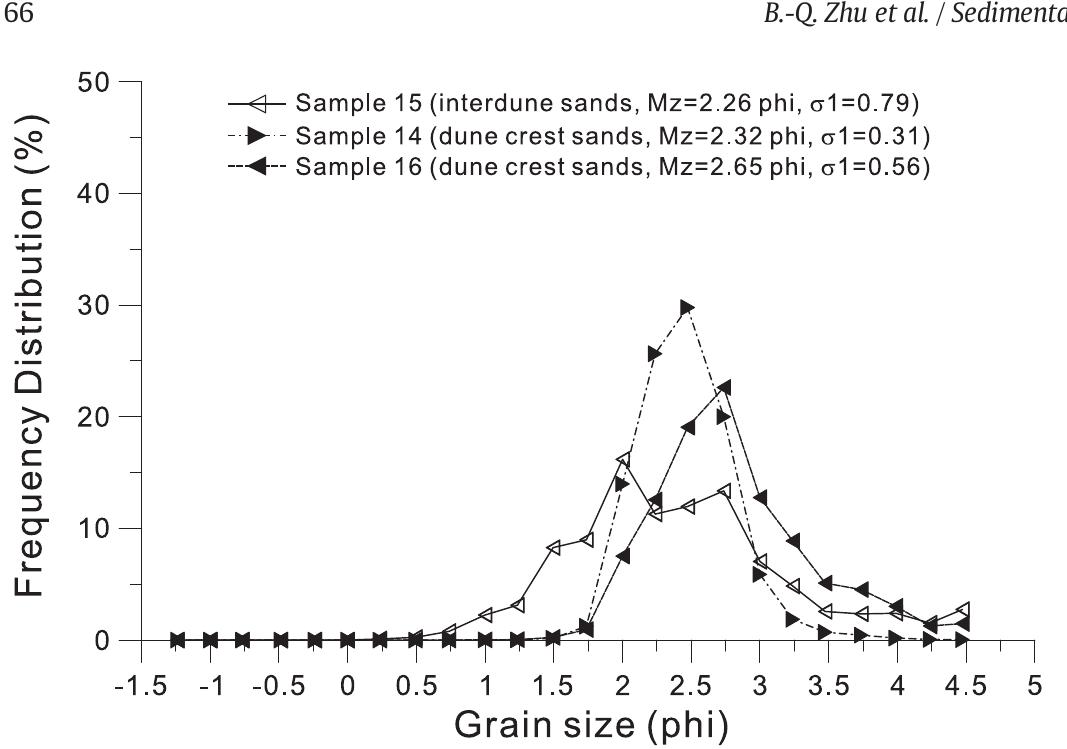

Fig. 11. Frequency distribution curves of grain size between interdune sands and nearby dune crest sands.

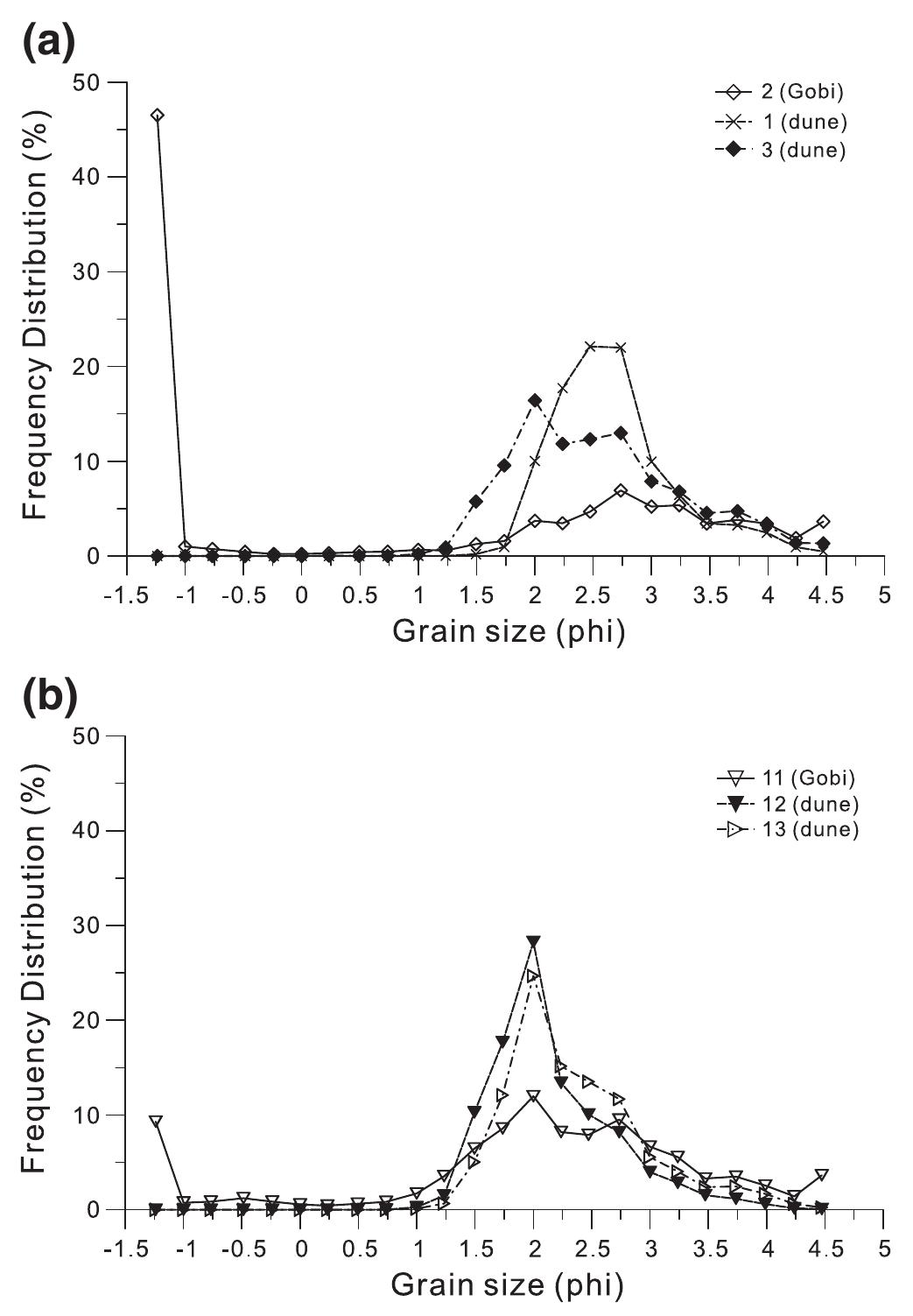

Fig. 12. Frequency distribution curves of grain size between Gobi sand and nearby dune sand.

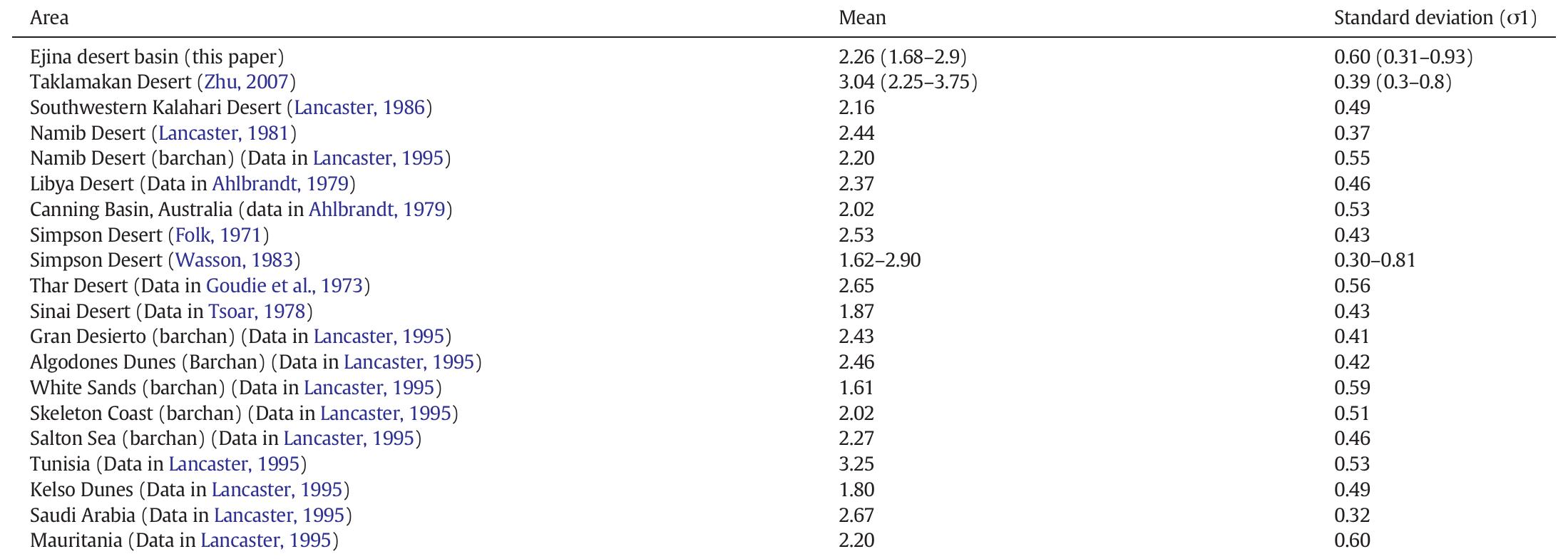

Grain size character of linear/barchan dune crest sands in different sand deserts (phi units).

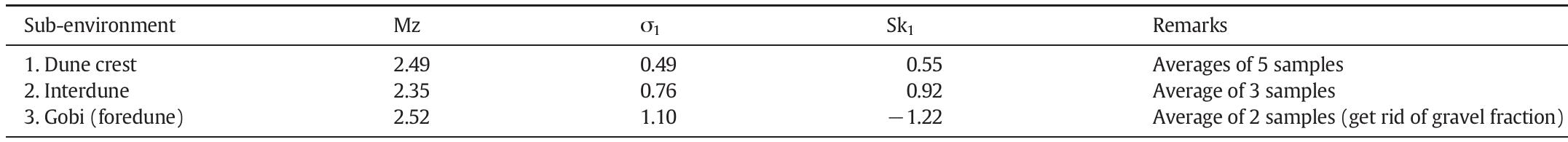

Grain size statistics from the sub-environments of dune unit in the Ejina Basin (data from this study). Table 4

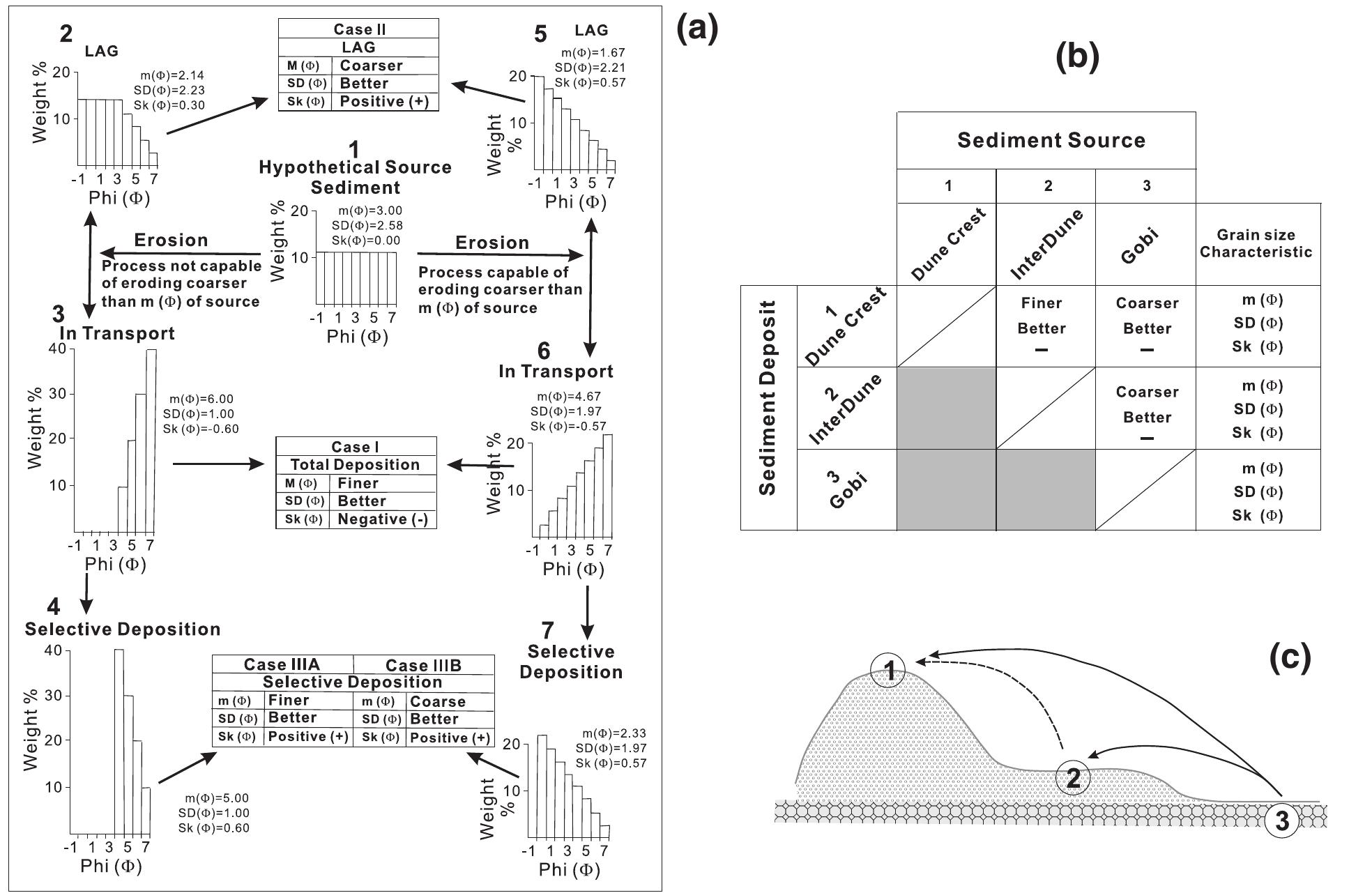

Fig. 13. (a) Histograms showing the changes in grain size distributions when a hypothetical source sediment is eroded, transported, and deposited (modified from McLaren, 1981). (b) A sediment trend matrix for desert sediments in the Ejina. The matrix of grain size relationships is from three sub-environments (Table 4). The mean grain size is finer, the same, or coarser, the sorting is better, the same, or poorer, and the skewness is more positive (+), the same, or more negative (—) when a possible deposits is compared to a possible source. Shaded boxes indicate trends that are impossible between a deposit and its source sediment based on the trends shown in Fig. 13a. (c) Sediment transport paths for the Ejina aeolian sys- tem that corresponding to Fig. 13b. Solid arrows denote Case III and dashes denote Case | in Fig. 13a.

(责任编辑:)

|